- Homepage

- Composition

- Denomination

- Ae Prutah (34)

- Ae3 (14)

- Antoninianus (104)

- Ar Denarius (42)

- Aurelianianus (12)

- Aureus (145)

- Bi Double Denarius (24)

- Bi Nummus (22)

- Centenionalis (16)

- Cistophorus (24)

- Denarius (1272)

- Double Denarius (63)

- Dupondius (16)

- Nummus (119)

- Prutah (27)

- Quadrigatus (13)

- Sestertius (127)

- Siliqua (15)

- Solidus (169)

- Tetradrachm (21)

- Other (604)

- Era

- Grade

- Ruler

- Antoninus Pius (53)

- Augustus (141)

- Caracalla (53)

- Constantine I (57)

- Constantine Ii (29)

- Domitian (58)

- Gallienus (37)

- Gordian Iii (62)

- Hadrian (100)

- Marcus Aurelius (69)

- Nero (113)

- Nerva (31)

- Philip I (66)

- Septimius Severus (36)

- Severus Alexander (69)

- Theodosius Ii (32)

- Tiberius (69)

- Trajan (97)

- Trajan Decius (28)

- Vespasian (76)

- Other (1607)

- Year

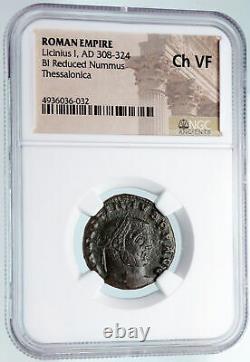

LICINIUS I Constantine I enemy 309AD Ancient Roman Coin NUDE Genius NGC i89695

Bronze Follis 23mm Thessalonica mint, struck 309-310 A. Reference: RIC VI 30b Certification: NGC.

Ch VF 4936036-032 VAL LICINIVS P F AVG, Laureate head right. GENIO AVGVSTI / (star)/ G /. TS - Genius standing left, pouring out patera and holding cornucopia. The cornucopia (from Latin cornu copiae) or horn of plenty is a symbol of abundance and nourishment, commonly a large horn-shaped container overflowing with produce, flowers or nuts.

The horn originates from classical antiquity, it has continued as a symbol in Western art, and it is particularly associated with the Thanksgiving holiday in North America. Mythology offers multiple explanations of the origin of the cornucopia. One of the best-known involves the birth and nurturance of the infant Zeus, who had to be hidden from his devouring father Kronus.

In a cave on Mount Ida on the island of Crete, baby Zeus was cared for and protected by a number of divine attendants, including the goat Amalthea ("Nourishing Goddess"), who fed him with her milk. The suckling future king of the gods had unusual abilities and strength, and in playing with his nursemaid accidentally broke off one of her horns, which then had the divine power to provide unending nourishment, as the foster mother had to the god. In another myth, the cornucopia was created when Heracles (Roman Hercules) wrestled with the river god Achelous and wrenched off one of his horns; river gods were sometimes depicted as horned.This version is represented in the Achelous and Hercules mural painting by the American Regionalist artist Thomas Hart Benton. The cornucopia became the attribute of several Greek and Roman deities, particularly those associated with the harvest, prosperity, or spiritual abundance, such as personifications of Earth (Gaia or Terra); the child Plutus, god of riches and son of the grain goddess Demeter; the nymph Maia; and Fortuna, the goddess of luck, who had the power to grant prosperity.

In Roman Imperial cult, abstract Roman deities who fostered peace (pax Romana) and prosperity were also depicted with a cornucopia, including Abundantia, "Abundance" personified, and Annona, goddess of the grain supply to the city of Rome. Pluto, the classical ruler of the underworld in the mystery religions, was a giver of agricultural, mineral and spiritual wealth, and in art often holds a cornucopia to distinguish him from the gloomier Hades, who holds a drinking horn instead. The Genius was a protection spirit, analogous to the guardian angels invoked by the Church of Rome. The belief in such spirits existed in Greece and at Rome. The Greeks called them Daemons, and appear to have believed in them from the earliest times, though Homer does not mention them. Hesiod says that the Daemons were 30,000 in number, and that they dwelled on earth unseen by mortals, as the ministers of Zeus, and as the guardians of men and justice. He further conceives them to be the souls of the righteous men who lived in the golden age of the world. The Greek philosophers took up this idea, and developed a complete theory of daemons. Thus we read in Plato, that daemons are assinged to men at the moment of their birth, that they accompany men through life, and after death conduct their souls to Hades. Pindar, in several passages of the spirit watching over the fate of man from the hour of his birth.The daemons are further described as ministers and companions of the gods, who carry the prayers of men to the gods, and the gifts of the gods to men, and accordingly float in immense numbers in the space between heaven and earth. There was also a distinct class of daemons, who were exclusively the ministers of the gods. The Romans seem to have received their notions respecting the genii from the Etruscans, though the name Genius itself is Latin (it is connected with gi-gn-o, gen-ui, and equivalent in meaning to generator or father). The genii of the Romans are the powers which produce life (dii genitales), and accompany man through it as his second or spiritual self.

They were further not confined to man, but every living being, animal as well as man, and every place had its genius. Every human being at his birth obtained (sortitur) a genius, who he worshipped as sanctus et sanctissimus deus, especially on his birthday, with libations of wine, incense, and garlands of flowers. The bridal bed was sacred to the genius, on account of his connection with generation, and the bed itself was called lectus genialis. On other merry occasions, also, sacrifices were offered to the genius, and to indulge in merriment was not unfrequently expressed by genio indulgere, genium curare, or placarae. The whole body of the Roman people had its own genius, who is often seen represented on coins of Hadrian and Trajan.

He was worshipped on sad as well as joyous occasions; thus, sacrifices were offered to him at the beginning of the 2nd year of the war with Hannibal. The genii are usually represented in works of art as winged beings. The genius of a place appears in the form of a serpent eating fruit placed before him. Licinius I Latin: Gaius Valerius Licinianus Licinius Augustus ; c. 263-325 was a Roman emperor from 308 to 324.

For most of his reign he was the colleague and rival of Constantine I, with whom he co-authored the Edict of Milan that granted official toleration to Christians in the Roman Empire. He was finally defeated at the Battle of Chrysopolis, before being executed on the orders of Constantine I.Sculptural portraits of Licinius (left) and his rival Constantine I (right). Born to a Dacian peasant family in Moesia Superior, Licinius accompanied his close childhood friend, the future emperor Galerius, on the Persian expedition in 298.

He was trusted enough by Galerius that in 307 he was sent as an envoy to Maxentius in Italy to attempt to reach some agreement about the latter's illegitimate political position. Galerius then trusted the eastern provinces to Licinius when he went to deal with Maxentius personally after the death of Flavius Valerius Severus. Upon his return to the east Galerius elevated Licinius to the rank of Augustus in the West on November 11, 308. He received as his immediate command the provinces of Illyricum, Thrace and Pannonia. In 310 he took command of the war against the Sarmatians, inflicting a severe defeat on them and emerging victorious.

On the death of Galerius in May 311, Licinius entered into an agreement with Maximinus II (Daia) to share the eastern provinces between them. By this point, not only was Licinius the official Augustus of the west but he also possessed part of the eastern provinces as well, as the Hellespont and the Bosporus became the dividing line, with Licinius taking the European provinces and Maximinus taking the Asian. An alliance between Maximinus and Maxentius forced the two remaining emperors to enter into a formal agreement with each other. So in March 313 Licinius married Flavia Julia Constantia, half-sister of Constantine I, at Mediolanum (now Milan); they had a son, Licinius the Younger, in 315.

The redaction of the edict as reproduced by Lactantius - who follows the text affixed by Licinius in Nicomedia on June 14 313, after Maximinus' defeat - uses a neutral language, expressing a will to propitiate "any Divinity whatsoever in the seat of the heavens". Daia in the meantime decided to attack Licinius. Leaving Syria with 70,000 men, he reached Bithyniaa, although harsh weather he encountered along the way had gravely weakened his army. In April 313, he crossed the Bosporus and went to Byzantium, which was held by Licinius' troops. Undeterred, he took the town after an eleven-day siege.

He moved to Heraclea, which he captured after a short siege, before moving his forces to the first posting station. With a much smaller body of men, possibly around 30,000, Licinius arrived at Adrianople while Daia was still besieging Heraclea. Before the decisive engagement, Licinius allegedly had a vision in which an angel recited him a generic prayer that could be adopted by all cults and which Licinius then repeated to his soldiers.On 30 April 313, the two armies clashed at the Battle of Tzirallum, and in the ensuing battle Daia's forces were crushed. Ridding himself of the imperial purple and dressing like a slave, Daia fled to Nicomedia. Believing he still had a chance to come out victorious, Daia attempted to stop the advance of Licinius at the Cilician Gates by establishing fortifications there.

Unfortunately for Daia, Licinius' army succeeded in breaking through, forcing Daia to retreat to Tarsus where Licinius continued to press him on land and sea. The war between them only ended with Daia's death in August 313. Given that Constantine had already crushed his rival Maxentius in 312, the two men decided to divide the Roman world between them. As a result of this settlement, Licinius became sole Augustus in the East, while his brother-in-law, Constantine, was supreme in the West. Licinius immediately rushed to the east to deal with another threat, this time from the Persian Sassanids. In 314, a civil war erupted between Licinius and Constantine, in which Constantine used the pretext that Licinius was harbouring Senecio, whom Constantine accused of plotting to overthrow him. Constantine prevailed at the Battle of Cibalae in Pannonia (October 8, 314).Although the situation was temporarily settled, with both men sharing the consulship in 315, it was but a lull in the storm. The next year a new war erupted, when Licinius named Valerius Valens co-emperor, only for Licinius to suffer a humiliating defeat on the plain of Mardia (also known as Campus Ardiensis) in Thrace. The emperors were reconciled after these two battles and Licinius had his co-emperor Valens killed.

Over the next ten years, the two imperial colleagues maintained an uneasy truce. Licinius kept himself busy with a campaign against the Sarmatians in 318, but temperatures rose again in 321 when Constantine pursued some Sarmatians, who had been ravaging some territory in his realm, across the Danube into what was technically Licinius's territory. When he repeated this with another invasion, this time by the Goths who were pillaging Thrace, Licinius complained that Constantine had broken the treaty between them. Constantine wasted no time going on the offensive. Then in 324, Constantine, tempted by the "advanced age and unpopular vices" of his colleague, again declared war against him and having defeated his army of 170,000 men at the Battle of Adrianople (July 3, 324), succeeded in shutting him up within the walls of Byzantium.The defeat of the superior fleet of Licinius in the Battle of the Hellespont by Crispus, Constantine's eldest son and Caesar, compelled his withdrawal to Bithynia, where a last stand was made; the Battle of Chrysopolis, near Chalcedon (September 18), resulted in Licinius' final submission. While Licinius' co-emperor Sextus Martinianus was killed, Licinius himself was spared due to the pleas of his wife, Constantine's sister and interned at Thessalonica.

The next year, Constantine had him hanged, accusing him of conspiring to raise troops among the barbarians. After defeating Daia, he had put to death Flavius Severianus, the son of the emperor Severus, as well as Candidianus, the son of Galerius. He also ordered the execution of the wife and daughter of the Emperor Diocletian, who had fled from the court of Licinius before being discovered at Thessalonica. As part of Constantine's attempts to decrease Licinius's popularity, he actively portrayed his brother-in-law as a pagan supporter. This was not the case; contemporary evidence tends to suggest that he was at least a committed supporter of Christians.He co-authored the Edict of Milan which ended the Great Persecution, and re-affirmed the rights of Christians in his half of the empire. He also added the Christian symbol to his armies, and attempted to regulate the affairs of the Church hierarchy just as Constantine and his successors were to do. His wife was a devout Christian. It is even a possibility that he converted. However, Eusebius of Caesarea, writing under the rule of Constantine, charges him with expelling Christians from the Palace and ordering military sacrifice, as well as interfering with the Church's internal procedures and organization.

According to Eusebius, this turned what appeared to be a committed Christian into a man who feigned sympathy for the sect but who eventually exposed his true bloodthirsty pagan nature, only to be stopped by the virtuous Constantine. Finally, on Licinius's death, his memory was branded with infamy; his statues were thrown down; and by edict, all his laws and judicial proceedings during his reign were abolished. World-renowned expert numismatist, enthusiast, author and dealer in authentic ancient Greek, ancient Roman, ancient Byzantine, world coins & more. Ilya Zlobin is an independent individual who has a passion for coin collecting, research and understanding the importance of the historical context and significance all coins and objects represent. Send me a message about this and I can update your invoice should you want this method.

Getting your order to you, quickly and securely is a top priority and is taken seriously here. Great care is taken in packaging and mailing every item securely and quickly. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic? You will be very happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing.

Additionally, the coin is inside it's own protective coin flip (holder), with a 2x2 inch description of the coin matching the individual number on the COA. Whether your goal is to collect or give the item as a gift, coins presented like this could be more prized and valued higher than items that were not given such care and attention to. When should I leave feedback? Please don't leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens sometimes that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for their order to arrive. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me.

My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service. How and where do I learn more about collecting ancient coins? Visit the Guide on How to Use My Store. For on an overview about using my store, with additional information and links to all other parts of my store which may include educational information on topics you are looking for.

This item is in the category "Coins & Paper Money\Coins: Ancient\Roman: Imperial (27 BC-476 AD)". The seller is "highrating_lowprice" and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Certification Number: 4936036-032

- Certification: NGC

- Grade: Ch VF

- Year: 309 AD

- Ruler: Constantine I

- Denomination: AE3 BI Nummus

- Era: Ancient